An inexpensive tactile Braille display and keyboard with reciprocity

| tags: blind, enabling technology, ideas, literacy

I describe an idea for a simple and inexpensive tactile display and keyboard for Braille. The key simplification enabling this design is displaying Braille on six finger tips instead of as six tiny dots under one finger tip. The display is arranged in the same format as standard Braille embossers so users read and write in a reciprocal fashion. The display and keyboard might be useful for teaching Braille to blind children, as a communication system for deaf-blind people, and as a reading aid for blinded adults whose fingers are not sufficiently sensitive to read traditional Braille.

Introduction

Refreshable Braille displays (Figure 1) for the blind, like most assistive technologies, are very expensive. Low production volumes and the mechanical complexity of moving many tiny pins are the most likely reasons for their high cost but many people who are blind go without a Braille display because of lack of money. At a recent workshop presented by "Bapin", Anindya Bhattacharyya, I started thinking about how we might more inexpensively display Braille.

Traditional manually operated Braille embossers (Figure 2) provide six keys for embossing the individual dots in a Braille cell and a central space bar. The user depresses the key for dot-1 with the left index finger, dot-2 with the left middle finger, dot-3 with the left ring finger, and dots 4,5 and 6 with the corresponding fingers on the right hand. Students learn to make dot-1 they must press with their left index finger. Suppose we used this linkage between dots and fingers to display Braille as well as to type it?

A web search taught me that this method of using a different finger to represent each dot is known as Finger Braille and is widely used in the deaf-blind community in Asia. In Finger Braille one person "types" Braille onto the fingers of another person just as if they were typing on an embosser[1]. Miyagi states that skilled deaf-blind people are able to receive 350 characters per minute using finger Braille.

Finger Braille might be easier for young children to learn than conventional printed Braille. Children are often confused by the need to read Braille in a 2x3 array and to write Braille with a 1x6 array.

A prototype implementation

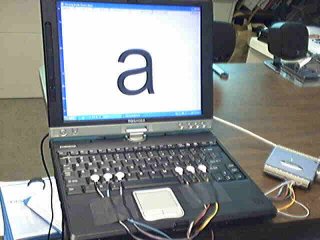

Figure 3 shows a crude prototype of the Braille display and keyboard. Tiny mechanical vibrators about the size and shape of an aspirin tablet are attached to 6 keys on an ordinary computer keyboard. On the prototype depicted here we used Z,X,C on the left and comma, period, slash on the right. The traditional "home" keys would likely be more comfortable for an adult sized hand. The vibrators are designed for use in pagers and cell phones, have no exposed moving parts, and are very inexpensive because they are produced in huge volumes. The computer controls the individual motors using a USB Digital interface from Measurement Computing (USB-1024HLS). The total hardware cost is under $200 in unit quantities.

Software on the computer allows typing Braille by depressing the keys for the appropriate dots. The dots are registered on release so they do not have to be depressed at exactly the same time. The computer displays Braille by gently vibrating the motors on the appropriate fingers. So, to make the letter B, the user presses down with the left-index and left-middle fingers while to display the letter B, the computer vibrates those same two fingers. The intensity and duration of the vibration is easily variable.

The software in our prototype implementation displays each letter visually, with speech, and on the vibrating keys. The user can type a letter and immediately feel it or first feel a letter and then type it. The software can record, playback, and print the sequence of letters the user has typed. Of course there is considerable room for improvement in this design.

Future work

Before testing with children we want to make the prototype more mechanically robust by moving the display to a conventional external USB keyboard and covering the keyboard with a acrylic shield so that only the six vibrating keys and the space bar are exposed. All the wiring will be placed out of reach under the shield.

We plan to experiment with different approaches for pacing the display of characters. Simply displaying each character for a fixed interval as in the current prototype may not be the best, especially for beginners. We believe the space bar might be useful for pacing; for example pressing space could mean move to the next letter. Likewise it might be useful to include a key to indicate move backward by one letter or word to allow reviewing what has already been displayed. Miyagi[2], explores the timing issues for finger braille.

For young blind children it might be appropriate to present the system as a game that shows the child which keys to press to make a letter. Our game Hark the Sound could easily be extended to enable this sort of Braille input and display.

Evaluation

Once we get a more robust prototype going we propose ask a few of our blind friends to play with it to see if they can reliably read Braille. Later we may pursue a formal evaluation.

References

[1] Manabi Miyagi, Masafumi Nishida, and Yasuo Horiuchi, Conference System using Finger Braille, Proceedings of GOTHI'05, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, CA, Oct 24-26, 2005.

[2] Manabi Miyagi, Yasuo Horiuchi, and Akira Ichikawa, Prosody Rule for Time Structure of Finger Braille, Proceedings of GOTHI'05, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, CA, Oct 24-26, 2005.

Credits

Many of the ideas here came from conversations with Karen Erickson and Gretchen Hanser of the Center for Literacy and Disability Studies and with Diane Brauner.